Saturday 23rd August 2025

ON THIS DAY....23RD AUGUST 1305

Today we remember Sir William Wallace, executed in London on this day in 1305. His death was brutal—hanged, drawn, and quartered—but his legacy endures as one of Scotland’s most powerful symbols of resistance, courage, and conviction.

Born around 1270, likely in Elderslie, Renfrewshire, Wallace came from the lesser nobility. His father, believed to be Sir Malcolm Wallace, held land but wielded little political influence. Wallace likely received a Church-based education, learning Latin and law, and trained in the martial skills expected of a young landowner. Though not a high noble, he was deeply rooted in the land and values of his people.

Wallace’s rise began in 1296, when King Edward I of England deposed Scotland’s King John Balliol and declared himself overlord. In response, Wallace led a band of rebels, famously burning Lanark and killing its English sheriff. His campaign grew rapidly—he drove out English officials from Scone, struck at garrisons between the Forth and Tay, and joined forces with Sir William Douglas.

His most iconic moment came at the Battle of Stirling Bridge in September 1297. Wallace and Andrew Moray, commanding a vastly outnumbered Scottish force, used the narrow bridge to their advantage and defeated the English. This victory electrified the nation. Wallace was named Guardian of Scotland, a title he held until his defeat at Falkirk in 1298, where English longbowmen proved devastating.

Despite the loss, Wallace continued his resistance. He travelled abroad—possibly to France—seeking support for Scotland’s cause. In August 1305, he was betrayed and captured near Glasgow, handed over to Edward I, and taken to London. At his trial, Wallace famously declared that he was not a traitor, for he had never sworn allegiance to the English king.

His execution was meant to crush the spirit of rebellion. Instead, it forged a legend.

Completed in 1869, the Wallace Monument stands atop Abbey Craig in Stirling, where William Wallace is said to have watched the English army before the Battle of Stirling Bridge. It was funded by tens of thousands of Scots—ordinary people, not nobles—who wanted to honour Wallace’s fight for freedom.

Designed in Victorian Gothic style by architect John Thomas Rochead, the 220-foot sandstone tower houses Wallace’s legendary sword. From its crown-shaped viewing gallery, visitors can see the very landscape where Wallace once stood.

Sunday 17th August 2025

At the beginning of World War I, Germany invaded neutral Belgium on 4 August 1914, using the country as an entry point to France. The Belgian army, after significant resistance, withdrew to the fortified city of Antwerp, where a large number of Belgian refugees had already taken shelter from the conflict. The Belgian army command considered abandoning Antwerp and moving the army south, contrary to British interests. Britain was concerned that German control of Belgian and French ports would disrupt connections with France and threaten British supply routes through the Channel.

Winston Churchill, then First Lord of the Admiralty, traveled to Antwerp on 2 October to encourage the Belgians to maintain their defense for as long as possible, providing Britain and France time to establish a defensive line in northern France. However, there were no available British or French troops to directly support the Belgians at that time.

During his journey, Churchill recognized that he could deploy three brigades under his authority, totaling approximately 6,000 men. The 3rd Royal Naval Brigade consisted of professional marines, while the 1st and 2nd Brigades were composed mainly of reservists and volunteers with limited training and equipment. On 4 October 1914, these forces were urgently mobilized to assist at Antwerp.

On 5 October, the 1st and 2nd Brigades arrived in Dunkirk and soon proceeded by train to Antwerp, where they were welcomed by the local population. They advanced to the front lines near the river Nete, where fighting took place on the same day. The engagement resulted in a retreat of both the Belgian and British forces to the outer ring of Antwerp’s forts. This allowed German heavy siege artillery to be positioned within range; the outdated fortifications were unable to withstand the bombardment, making the fall of Antwerp imminent.

To avoid encirclement, it was decided that the field army and British Brigades would withdraw across the Scheldt on the night of 8 October. The British troops were scheduled to travel by train to Ghent. Due to communication issues, Commodore Wilfred Henderson, commanding the 1st Royal Naval Brigade, did not receive orders to leave immediately. Later, upon learning of the destruction of railway lines and the German advance, Henderson determined that evacuation to Ghent was no longer feasible. He chose to cross into the Netherlands, resulting in internment according to international law for the remainder of the war.

Upon crossing the Dutch border, the troops were disarmed and informed they would reside in a guarded camp for the war’s duration, in accordance with international law provisions preventing them from rejoining hostilities. More than 30,000 Belgian soldiers also entered the Netherlands and were interned during 1914–1918.

The British spent their first night in the Netherlands outdoors before being transported by train to Terneuzen and then by ship to Vlissingen. A group of about 500 continued to Leeuwarden, while approximately 1,000 were sent to Groningen.

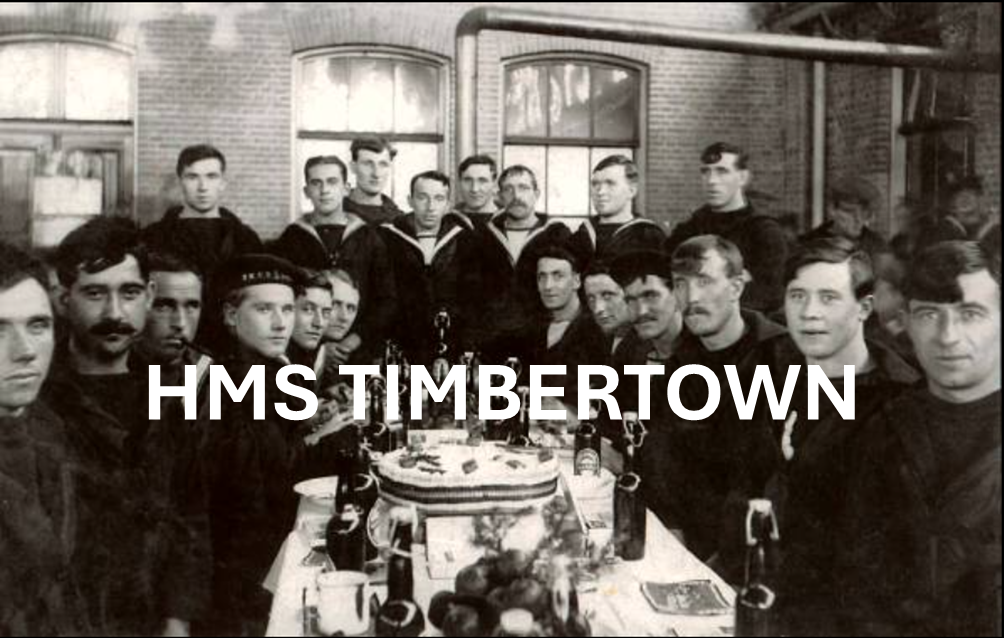

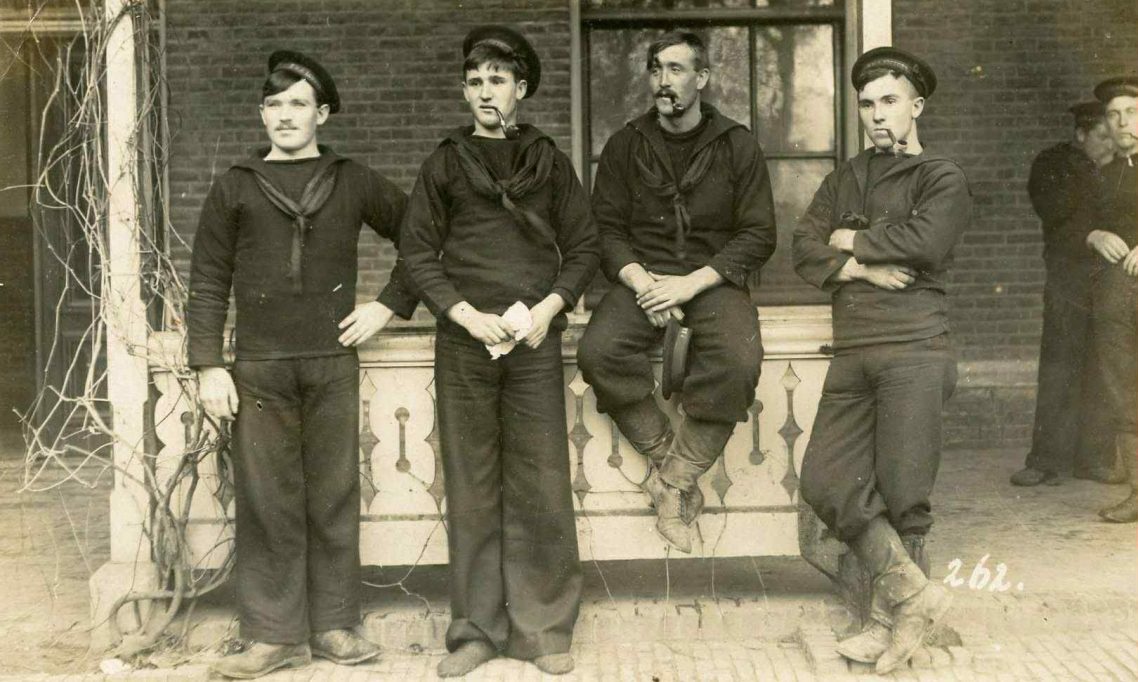

"HMS Timbertown" was the term used by British sailors for the wooden-hut internment camp built near Groningen, in the neutral Netherlands, following the retreat from Antwerp. Around 1,500 members of the 1st Royal Naval Brigade were interned there according to international law. Locals referred to the site as the "English Camp," while the nickname "Timbertown" referenced its wooden construction.

By early 1915, the camp featured facilities such as a post office/library, sports hall, medical area, recreation room/church, and rations supplemented by parcels and a camp budget. Daily activities included exercise, work or study, and limited evening outings to the city. Sundays were reserved for religious services.

Sports and cultural activities were organized, including football, rugby, athletics, boxing, cricket, and performances by groups like the "Timbertown Follies." The camp also produced items such as knitted uniforms and woodwork for sale, helping fund additional supplies. Public visits were permitted on some Sundays.

From April 1915, internees were allowed to perform paid, non-military work due to labor shortages in the Netherlands. Early escape attempts occurred, occasionally with local assistance, leading to diplomatic issues. By 1916, the British government began returning escapees to uphold Dutch neutrality. Over time, camp regulations relaxed, permitting compassionate leave and, later, group home leave on trust.

The story has a strong Hebridean thread. Contemporary research tied to the BBC ALBA documentary HMS Timbertown records that about 102 of the 1,500 internees were from the Isle of Lewis—a striking concentration for one island community. The grandfather of one of our followers, Margaret Stewart was one of those from Lewis interned there. Donald Graham, 71 Coll, Isle of Lewis was born on 18th October 1891 and was the son of Alexander Graham and Margaret MacRae. He enrolled with the Royal Naval Reserve on 28th January 1910, and his war service stretched from 5th August 1914 to 6th March 1919. He continued to serve with the Royal Naval Reserve until 1935.

Donald married Margaret MacLeod of 55 Coll on 26th December 1929. They went on to have two children, Alex Angus and Agnes (Margaret’s mother).

Donald features in both photographs. In the first he is 3rd from the right and in the second he is seated. Both photographs were taken at HMS Timertown. Thank you to Margaret Stewart for sharing these brilliant photographs.

The BBC Alba Documentary can be viewed below....

Sunday 10th August 2025

The story of Scotland’s canals isn’t just about boats and locks—it’s a tale of bold engineering, industrial dreams, and the lives woven along the watery corridors. These were not idle ditches; they were superhighways carved by hand and vision, built to move coal, timber — and people.

The dream of Scottish canals began with a problem: how to efficiently move bulky goods across unforgiving terrain. Roads were primitive, and rivers unpredictable. The solution? Artificial waterways.

The Forth and Clyde Canal (1768–1790): Scotland’s first major canal, envisioned by John Smeaton and completed by Robert Whitworth. Running 35 miles, it linked the River Forth at Grangemouth to the River Clyde at Bowling. Glasgow’s ascent as an industrial powerhouse was inseparable from the coal, iron and timber that flowed through this liquid artery.

The Caledonian Canal (1803–1822): A heroic feat led by Thomas Telford. Stretching 60 miles through the Great Glen, it connected Inverness to Fort William—using lochs and manmade channels. While intended to serve seagoing vessels and boost Highland trade, it suffered from being too shallow and narrow for evolving ship designs.

The Union Canal (1818–1822): Designed by Hugh Baird, this level canal snaked 31 miles from Falkirk to Edinburgh with no locks—elevated engineering in every sense. It aimed to bring coal directly into Edinburgh, joining the Forth and Clyde Canal via the Falkirk basin.

The canals were built by “navvies”—manual labourers known for brute strength and staggering endurance. They hacked through rock, clay and marshland using picks and shovels, often sleeping rough and living transient lives.

Work crews lived in makeshift huts, moved from section to section, and developed their own culture—marked by fierce camaraderie, local folklore, and sadly, dangerous working conditions.

Locks and aqueducts were the miracle tech of the day. The Avon Aqueduct near Linlithgow still stands as Scotland’s longest and tallest, built with daring ambition.

Once opened, the canals transformed commerce.

Coal from Lanarkshire powered the blast furnaces and steam engines of Glasgow and Edinburgh. Whisky barrels and grain headed out from rural distilleries to the ports. Timber and slate from the Highlands travelled south to build cities.

They also changed how people lived—lockkeepers, boatmen, warehouse crews, and canal-side traders formed close-knit communities. Inns and shops sprang up along towpaths.

By the late 1800s, railways overtook canals. Trains were faster, cheaper, and more flexible. Many canals were abandoned, drained, or allowed to decay.

But in the late 20th century, restoration began. The Falkirk Wheel (opened 2002) reconnects the Union and Forth and Clyde Canals—a stunning rotating boat lift symbolizing canal rebirth. Recreational use surged, with canal walks, wildlife spotting, kayaking, and heritage tourism breathing new life into old waters.

Scotland’s canals are more than historical footnotes. They are mirrors of its industrial spirit, its community resilience, and its willingness to carve beauty from engineering.

Friday 1st August 2025

Each August, beneath the majestic silhouette of Edinburgh Castle, thousands gather to witness a spectacle unlike any other: the Royal Edinburgh Military Tattoo. But this world-renowned event isn't just a performance — it's a story woven from Scotland’s proud military traditions, cultural resilience, and global connections.

The word “tattoo” doesn’t refer to body art but harks back to the 17th-century Dutch phrase doe den tap toe — “turn off the tap.” It was a signal for tavern keepers to stop serving so soldiers could return to their barracks. Over time, these nightly rituals evolved into full-blown military displays.

Scotland first hosted an official "Military Tattoo" in 1949 as part of the Edinburgh International Festival. It was modest — just eight military bands performing in Princes Street Gardens. But the concept struck a chord.

In 1950, the first formal Edinburgh Military Tattoo was staged on the Esplanade of Edinburgh Castle. It drew nearly 6,000 spectators, with massed pipes, drums, and highland dancers igniting patriotic fervour. The event’s location, flanked by history, gave it gravitas and symbolism — linking Scotland’s martial past with contemporary pride.

By the late 1960s, it had earned royal patronage and international acclaim. Its broadcasts reached millions across the globe, showcasing not only British forces but performers from allied nations — a nod to cooperation and peace after the hardships of war.

Today’s Tattoo is more than a military display — it’s an intercultural celebration. Countries from New Zealand to Nigeria have taken part, bringing drumming troupes, ceremonial dancers, and acrobatic displays to the Castle Esplanade.

The themes often reflect current global conversations — unity, heritage, remembrance — all expressed through carefully choreographed sound and movement.

While the event is steeped in history, it’s never static. Recent editions have incorporated advanced lighting effects, projections onto the castle walls, and contemporary music arrangements. Yet, the massed pipes and haunting solo piper closing the night remain sacred highlights.

For many, attending the Tattoo is a rite of passage — a moment of awe, pride, and connection. Veterans find recognition, performers share their heritage, and spectators carry home the echo of bagpipes beneath the stars. The Tattoo donates millions to military charities, preserving its purpose beyond performance.

While the Tattoo dazzles with military precision and theatrical flair, its roots stretch deep into the genealogical soil of Scotland. Beneath every tartan and behind each regiment lies a tapestry of ancestral stories — families who have carried tradition through centuries of service, artistry, and cultural preservation.

In the vibrant swirl of kilts and the resonant cry of bagpipes, the Royal Edinburgh Military Tattoo becomes more than a performance — it transforms into a living archive of Scotland’s families. Every march across the Esplanade echoes with ancestral footsteps, reminding us that heritage is not just remembered, but performed and passed on. Whether through regiment, tartan, or tune, historical families continue to shape the Tattoo's soul — one generation at a time.

Do you have ancestral ties to one of Scotland’s regiments? Did a grandparent play the pipes on the Esplanade, or does your family's tartan feature in the Tattoo’s dazzling mosaic? If the Tattoo has touched your heritage or inspired your family in any way, we’d love to hear your story. Share your connection — whether it’s a marching memory or a genealogical discovery — and help us add new voices to this living legacy.

Friday 25th July 2025

As Donald Trump touches down, it feels timely to reflect on his links to Scotland. Most are aware that Trump’s mother, Mary Ann MacLeod, hailed from the village of Tong near Stornoway on the Isle of Lewis. But while researching for the Vatisker Diaries book, I discovered a deeper family link that stretches beyond Tong and into the nearby village of Vatisker.

Mary Ann’s grandfather, Alexander MacLeod, was born around 1830 in Vatisker, part of the Back District of Lewis. He was the son of William and Christina MacLeod, residing at number 25 Vatisker. Alexander married Ann MacLeod of Tong in December 1853, and the couple settled at 25 Aird Tong. Their son, Malcolm MacLeod, wed Mary Smith, and they raised ten children at 5 Tong—the youngest being Mary Ann, born in 1912.

Trump’s great-grandfather Donald Smith tragically drowned in a fishing accident off Vatisker Point, near Stornoway on the Isle of Lewis, in 1868. A sudden squall overturned his open boat, claiming his life at just 34 years old. Two other men also perished, while two survived the ordeal.

His widow, Mary Smith, was left to raise their children alone, including Mary Smith, Trump’s grandmother. It’s believed that Donald Trump may have been named in memory of his great grandfather.

Like so many of her contemporaries at 18, Trump’s mother, Mary Ann left Lewis for the United States in 1930. She met Fred Trump, and they married in New York in 1936. She became a U.S. citizen six years later. In 2008, Donald Trump made a brief visit to the family home in Tong—a gesture so fleeting that it left many wondering whether it was a heartfelt homage or a calculated photo opportunity.

Today, Trump’s most visible Scottish footprint is his golfing empire. His Trump International Golf Links opened in Aberdeenshire in 2012, sparking controversy over its environmental impact. During its planning battle, Trump reflected: “If it weren’t for my mother, would I have walked away from this site? I think probably I would have, yes.” His Scottish holdings expanded further with the acquisition of Turnberry in Ayrshire in 2014.

Whether Trump’s ties to Lewis and Scotland are a guiding compass or simply a footnote in a larger-than-life story, his ancestral roots remain firmly planted in Hebridean soil. The journey from 25 Vatisker to the corridors of power reminds us that history often travels quietly through generations before taking centre stage. And as the waves brush the shores of Gress Beach, the legacy of the MacLeod family continues to ripple outward—etched into both local memory and global headlines.

Thursday 17th July 2025

If you had ancestors who lived in the central belt of Scotland, there is a good chance you will have ancestors who were employed in the coal mining industry. The history of Scottish coal mining spans over 800 years and significantly contributed to Scotland’s economic, industrial, and social development. The earliest records date back to the 12th century when monks at abbeys, such as Dunfermline Abbey, used coal from surface outcrops for heating.

From the early 1600s until the Coal Mines Act of 1799–1800 abolished it, miners and their families were legally bound to their masters' collieries for life, a system known as bondage. Working conditions were extremely dangerous without proper support, lighting, or ventilation. Workers often used their bare hands and spent long hours crouched or crawling.

In the late 18th to 19th centuries, coal became essential for the iron and steel industries, railways, and steamships. Deep mining expanded rapidly in Lanarkshire, Fife, Ayrshire, and the Lothians. Towns such as Airdrie, Coatbridge, and Motherwell developed around mining and heavy industry. Miners worked 10 to 12 hours a day, six days a week. Mechanisation began slowly, and there were frequent mining disasters. Black lung disease (pneumoconiosis) was widespread.

Prior to the Mines and Collieries Act 1842, the typical starting age for miners was between five and seven years old. Women and young girls were also found working in the pits. The 1842 Act raised the minimum age for boys to work underground to ten years old and prohibited women and girls of any age from working underground. In the early 20th century, the typical minimum age was 14-16 years old.

Coal mining accidents were tragically common, especially in Scotland’s deep pits during the 19th and early 20th centuries. The major contributors to these disasters were explosive gases, poor ventilation and flooding. Poorly supported mine roofs all too often caved in, crushing workers beneath tons of rock.

By far the worst coal mining disaster in Scotland’s history occurred on 22nd October 1877 in Pits No. 2 and No. 3 of William Dixon's Blantyre Colliery in Blantyre. An explosion killed in the region of 207 miners, with the youngest being a boy of 11. It is believed the accident left 92 widows and 250 fatherless children.

Despite the harsh working conditions and obvious dangers coal mining was pivotal to the development of Scottish industry and thereby the livelihoods of a large part of the population. It was not just the significant number of our workforce who were employed directly in the mines. Coal powered the other heavy industries that were developing at the time – iron and steel, shipbuilding, railways and steam shipping.

It was also important in the social development of the population. Mining communities developed strong local identities, traditions, and a shared sense of resilience. Institutions like miners’ welfare halls, brass bands, and football clubs (e.g. Motherwell F.C.) emerged from these social roots.

By 1913, Scotland had over 140,000 coal miners producing 43 million tons of coal annually. Conditions had improved with better lighting and ventilation, but the mines remained wet, cramped, dark, and noisy. Trade unions began advocating for better wages and conditions. As a result, mechanised cutters and conveyors became more common in larger pits, while surface levels improved significantly.

In 1947, the UK government nationalised the coal industry, creating the National Coal Board. Mechanisation and new technologies were introduced, improving output but reducing jobs. The legal minimum age was raised to 16 years old. Under the National Coal Board, safety training became compulsory. Medical care and welfare improved with more pithead baths and medical checks. However, miners still faced long hours, noise, physical strain, and occupational diseases.

Demand for coal declined due to oil, gas, and nuclear power. Many pits became uneconomical, especially smaller or deeper ones, leading to major pit closures throughout the 1960s to 1980s. Scotland's last deep coal mine, Longannet in Fife, closed in 2002.

Wednesday 9th July 2025

This week I am bringing you a story of a family reconnecting with a long-lost close relative that is described in a book I acquired recently from Lanarkshire Family History Society, called ‘Harthill – The Village That Went to War’. The village of Harthill in North Lanarkshire is where I live and was brought up.

The book remembers those who served during World War 1 who had some connection to the village of Harthill. There are so many great tributes in this book but one in particular has stood out to me. Every so often you read or hear something that just seems to resonate with you. In this line of work this happens regularly. I always find myself compelled to carry out some further research in these cases and here is the summary of what I personally collected and what I read in the book. I hope you find the story of Sgt David Alexander Kitto as interesting as I did.

He was born on 26th September 1885 at Braefoot, Carnoustie, the son of Thomas Kitto and Margaret Shands. He was the second oldest of a family of six. Although he started out his working life as an apprentice plumber (1901 census), he went on to gain a BSc in Chemistry from St Andrews University and found his way to Harthill, Lanarkshire where he became a teacher of science at Harthill Public School. In June 1915 he joined the Royal Army Medical Corps.

He met Isabella MacLure at teacher training college, and he took a short period of leave to marry her on 28th October 1915 in Dundee. Isabella was also a teacher at Harthill but returned to Arbroath and became a well-known teacher at Arbroath Primary School. She never remarried and died on 25th August 1979 at the age of 88 years.

David was promoted to Sergeant and in May 1916 he was sent to France. In November 1917 he was serving with the 37th Field Ambulance and was part of the British offensive known as the Battle of Cambrai which began on 20th November. Cambrai was a British attempt to take advantage of a perceived weakness in the German Hindenburg line. It was the first time tanks were used to spearhead the attack rather than the traditional artillery. The British attacked on a six-mile front to the west of the town, achieving initial success. However, they were unable to dislodge German artillery and infantry from the hills dominating the advance and enemy reinforcements, which were rushed to the area mounted a counterattack on 30th November. During the first day of the counterattack David was killed by a shell at Bourlon Wood. He was 32 years old. His body was not recovered, and his family were left unaware of his whereabouts. In the end the battle resulted in 80,000 German and 42,000 British casualties. David’s name was listed among the missing on the memorial at Cambrai.

In early 1990 the remains of RAMC shoulder flashes, a razor, a watch and a pen knife were ploughed up by farmers near the village of Villers-Plouich, near Cambrai. The farmers contacted the authorities, and permission was granted for further excavation. Human remains were discovered and following extensive research, the remains were found to be David’s. Although his wife was deceased, his brother-in-law, Adam MacLure, aged 90 years was located and his family helped with the arrangements for the funeral. The funeral took place on Friday 11th June 1993 at Terlinethun British Cemetery, near Wimille in the Pas-de-Calais region. The funeral was held according to the rites of the Church of Scotland and Sergeant Kitto’s regiment provided the bearer and saluting party, all the men coming from the 2nd Armoured Field Ambulance, RAMC, based in Osnabruck, Germany. Civil representatives of the British and French governments were present as he was buried with full military honours.

David’s nephew, Neil MacLure said

“David Kitto was thought of often in our home. We were very much aware of the fact that he had died in the first world war at a place unknown and that no trace of him has ever been found. As children, we came with our father often to France and we visited many war cemeteries looking for a trace of him. Today is very much the closing chapter”.

Monday 30th June 2025

Hello and a warm welcome to my very first Kith and Kin post! I’m absolutely thrilled to have you with me. It’s a bit of a dream come true as I finally kick off my new genealogy adventure, Kith and Kin Scottish Ancestry.

Firstly, let me explain about the name. The term ‘kith and kin’ is commonly used in Scotland to describe the people you are connected with, your family and friends.

In an increasingly fast-paced and globalised world, more people are turning inward to explore where they come from — not just culturally, but personally. The study of family history can have deep emotional, historical, and even medical value.

So why does it matter? What do we really gain by tracing our roots?

At its core, genealogy helps answer one of life’s most fundamental questions: Who am I? Learning about your ancestors — where they lived, how they lived, what they experienced — can foster a deeper connection to your own identity. It gives context to your cultural heritage, traditions, and even the values passed down through generations. Understanding your roots can also instil a sense of belonging.

Understanding your own heritage personalises history. It turns abstract dates and distant events into lived experiences.

Discovering that your great-grandparents were immigrants fleeing hardship, or that a relative fought in a historic war, can change the way you view the past. When doing my own family research, I found myself bursting with pride at what all of my ancestors achieved. It is because of their story that I persist and now I understand where I came from, I realise that their story is actually part of mine.

Instead of reading about history in textbooks, genealogy allows you to feel it through your family’s unique narrative. This connection makes history more tangible, relatable, and impactful.

I started my genealogy journey back in 2008. I was very close to my maternal grandmother before she passed away in February 1994. In July 2009 she would have celebrated her 100th birthday and I wanted to mark that occasion in some personal way. So, I started to compile her family tree. This experience enriched my own life in so many ways – when you piece together the individual lives of family members it gradually reveals a family story – the highs and lows that would have touched the whole family. Several of my grandmother’s siblings emigrated to Canada, USA and Australia at a very young age. Researching emigration records, census records and other records from their new country of residence helped shine a light on their new lives. I visited Vancouver in Canada to follow in the footsteps of my grandparents who met and lived there in the late 1920s to mid-1930s. I had no idea what life was like for them in Canada at that time and began to read about that period. I learnt about the Great Depression and the associated hardships, the key events that were going on in Vancouver over that time period. Things they would have known about or experienced first-hand. I was able to discover the resting place of my grandmother’s brother and to visit. She never had the opportunity to do so, and I felt privileged to be able to lay flowers there on her behalf. I actually got access to his medical records in Canada. He had no wife or children, and it was comforting to know that one of his other sisters visited him a number of times in hospital before he passed. I discovered another brother lost his life in Egypt during World War I and I researched his regiment and the events that led up to his death. Whilst in Canada my grandparents had two children. After returning to Scotland their son sadly passed away, aged 3 years. Through searching cemetery records and liaising with the local authority I was able to pinpoint his grave. It was a poignant and fulfilling experience to be able to take my mother there. Through this experience I realised that history is a series of coincidental events that lead you to the present. Had my grandparents not met in Vancouver I wouldn’t be here today.

My maternal grandfather was born in a small village called Vatisker on the Isle of Lewis. Having discovered my grandmother’s roots I realised I knew very little about my ancestors in Lewis or indeed what life was like there. So, I started to build my Lewis family tree and understand the events that shaped their lives over time. At the time I could find little information on the village, so I embarked upon one of the most fulfilling experiences of my life. I wrote a book called Vatisker Diaries on the history of the village. This was published in collaboration with the local history society in 2023. Understanding each family in the village and the events that shaped their lives really helped me understand my Lewis roots. On a personal note, I never met my grandfather as he passed away before I was born. This was my way of connecting with him in ways I sadly didn’t have the opportunity to in person.

Through my work on Vatisker I have gained valuable experience as a genealogist. I have made so many wonderful personal connections with people from all over the world who had Vatisker connections and best of all I have produced an artefact that will outlive me, and I hope it serves as a reference and inspiration to others in the years to come. I relished this experience so much I have embarked on my next village history.

There is never an end to family history research. As we traverse our lives, we all leave footprints. These can be formal records, newspaper articles, photographs, journals or simply the memories that live in others we have shared our lives with. Over the course of time new sources become available, and you can build your picture even more. Only recently I have developed my paternal family tree to a state where I feel I now understand that side of my family history to a reasonable level. It is enriching to be able to share that with my father who has been delighted to learn of relatives who emigrated to the USA and their lives there. It is powerful to reignite fond memories of old family members who are no longer with us. Discovering newspaper articles that tell the story of significant events in our family history can help take us back in time and kindle emotions within us as we feel what those experiences were like for our family. With my paternal family almost all roads lead to Ireland and although I haven’t really dipped my toe much in Irish genealogy yet it is definitely on my to do list.

I am going to sign off with what I consider the most fulfilling outcome of my family history experience.

Back in September 1969, my parents welcomed my elder brother, John, into the world, but tragically, he lived just 10 minutes. Born and passing on the 8th of September in Lanark, my parents were heartbroken and, at the time, weren’t told where he was laid to rest.

Fast forward nearly four decades and buoyed with the success of finding my aforementioned uncle’s grave, I decided to contact South Lanarkshire Council. To my surprise, they emailed me back with the news that John rested in a specific part of Lanark Cemetery. We decided to create a small memorial for John, crafting a special space among other memorials to honour his short life. It was a beautiful moment when my parents laid the memorial stone, surrounded by immediate and extended family. Just a few weeks later, on 8th September 2009, my family gathered once more on the occasion of what would have been his 40th birthday. For the first time ever, we were able to feel physically close to him as we commemorated his birthday.

My mother passed away in October 2022, and we laid another little memorial stone next to John’s. My father visits regularly, tending to both of their memorials as well as those of the other children in the vicinity. He makes sure it’s a lovely spot filled with flowers. I often think, had I not started on my family history journey, we might have missed this precious opportunity. My mum would have left this world without ever knowing where her first child rested, and we wouldn’t have such a special place to feel a connection with both of them.

The power of family history research is something I cherish dearly. It is truly a magical experience. Genealogy is more than a collection of names and dates. It’s a window into your past that can illuminate your present and even influence your future. Whether you’re diving into old census records, building a family tree, or taking a DNA test, the journey of discovering your roots is one that offers deep, lasting value.

In learning about where you come from, you might just discover more about who you are — and who you want to become.